| |

A Cross of Churches Around Conrad' s Heart: An analysis of the function and symbolism of the Cross of Churches in Utrecht, and those of Bamberg and Paderborn*

by Aart J. J. Mekking

THE FOUNDATION OF THE CROSS OF CHURCHES IN UTRECHT: THE HlSTORI CAL SETTING OF THE FOUNDATION AND lTS PATRONS

'In the year 1039 after the incarnation of Our Lord', emperor (1027-39) Conrad (II), seeing that nearly everything in his kingdom was going according to his wishes, was celebrating holy Whitsun (June 3) in Utrecht, a city in Friesland, in the confidence that his son -now that his kingship had become reality- might hope for the emperorship. As he strode to the table while celebrating the most holy festival in great splendour with his son and the empress, the crown on his head, he appeared in some pain which he nonetheless endured. When the following day the illness, which would prove fatal, struck violently and the Bishops present in Utrecht gathered around his deathbed at his request, he had the body and blood of the Lord and the Sacred Cross with the relics of the saints brought to him. All in tears he raised himself up and received the last sacraments and the absolution of his sins through a pure and sincere confession and a fervent prayer that he carried out with the greatest possible humility. He thereupon bid farewell to the empress and to his son king Henry after having admonished him with all his heart. Then he died on (Whit) Monday, the fourth of June in the seventh indiction. The emperor's remains were interred in Utrecht and the king enriched the burial place with gifts and inalienable goods,’ 1

King from 1039 and emperor between 1046 and 1056, Henry III seems to have had a very strong bond with his father Conrad.2 Perhaps for this reason he remained so weIl disposed towards Utrecht, the city in which his beloved father's remains were interred (Pl. VIA). No other king or emperor of the Holy Roman Empire visited as of ten the episcopal see to attend the solemn celebration of the great feasts there.3 Henry's generosity towards the church of Utrecht is accounted for by a document of 21 May 1040: 'We have entrusted the entrails of our father to Martinus as a precious deposit, so that we are now in his debt'. This is followed with a list of the rich gifts bestowed upon the church of Bishop Bernold (1027-54).4

The entrails were regarded as the most important parts of the body. The source of all life was believed to be contained in the entrails. The heart, the most important of all entrails, was thought to be the seat of the soul and of the mind, which joined the soul to the body.5 This may explain Henry's devotion to, and patronage of his father's final resting place; it was Henry's wish that his own heart and entrails be buried in his favourite place, at Goslar, his 'patria' and 'lar domesticus'.6 The annals of Pöhlde describing Henry's death say that he on 5 October 1056, from his deathbed in Bodtfeld,

* Translated from Dutch by K. Ronnau-Bzadbeer

(100)

ordered that his remains be transferred to the imperial family's funerary oratory at Speyers.7

Just as the entrails of his father were deposited in a tomb before the high altar of the Utrecht Cathedral,8 so Henry's heart and entrails were interred in front of the high altar of the monastery of Simon and Judas in Goslar, which he himself founded. According to the annals of Pöhlde, Henry instructed that his heart be buried there, 'because his heart had always been there', but his heart also went out to the place where the heart of his emperor and father was interred.

The affection of Henry III for his father Conrad II of which the sources speak was, in my opinion, the impetus for the foundation of the cross of churches in Utrecht. It was not built around the oldest cathedral, the venerabie Salvator, upon which the new churches depended.1O Nor did the cathedral precinct lie in the centre of the cross. Rather it was the Cathedral of St Martin where the most important physical remains of the first Salic emperor lay which lay at the heart of the cross of churches. This configuration expresses Henry's design: to establish a cross of churches around Conrad's heart, just as his father's predecessor Henry II had himself buried at the centre of a cross of churches he founded for the purpose at Bamberg.

That the foundation of a cross of churches at Utrecht was carried out at the initiative of Henry III may be apparent from the consecration of altars to the king's chosen patron saints, Simon and Judas (Pl. VIB). One of the altars is preserved in the eleventh century cathedral, the other in the Pieterskerk. The latter is particularly significant as the Pieterskerk may have been the first in the sequence of churches to be built.

According to one tradition, the Pieterskerk in Utrecht was consecrated on 1 May 1048. This tradition (one of the very few that have a hearing on the time of construction of the eleventh-century church in Utrecht), fits well with the widely accepted belief that the cross of churches in Utrecht was founded shortly after 1039. The intervening period of seven or eight years must have been more than enough to build at least one church.12

Two passages from medieval texts suggest that Bishop Bernold himself was active in the establishment of a cross of churches in the 'capital' of his bishopric. The following statement, which must be dated to 1050 and which refers to the construction of the Paulusabdij (Paul's Abbey), appears in the earliest of two texts: '(. . .) I, the unworthy person of Bernold, Bishop of the see of Utrecht, have had built a monastery in the southern part (meridiana plaga) of this same city'.13 One could infer from the choice of words used to describe the location of the Paulusabdij, that the author's conception of the layout of the city is informed by its arrangement around the four cardinal points of the compass; churches built on these points had the effect of notionally dividing medieval cities into quarters.

The second passage, from the Ordinals of the Cathedral which is dated to 1200, deals with the first vespers of the evening before the feast of the Invention of the Cross (3 May). On this evening the canons of all the chapters joined in solemn procession to the cathedral in order to celebrate liturgical offices before the great reliquary-cross there.14

It appears to me that a connection may exist between this custom and the choice of the first of May (1048) for the consecration of the Pieterskerk. The intention may have been to move from the newly consecrated church to the Cathedral for vespers on the evening of 2 May to return to the Pieterskerk for the rites of the feast of the Invention of the Cross on 3 May.15 The procession on the evening of 2 May, which continued in later centuries, was without doubt intended to express the close relationship between the collegiate churches and the cathedral in elaborate and public liturgy.

(101)

The most significant aspect of all this is, however, that both the procession and the consecration of the Pieterskerk were held on the most important feast of the cross in the western church's calendar, the Invention of the Cross. However, the choice of this feast for the consecration of the Pieterskerk is not accidental.16 The ceremonies scheduled for the first three days of May 1048 mark not only the consecration of the Pieterskerk, but announce the official installation of the cross of churches in Utrecht.

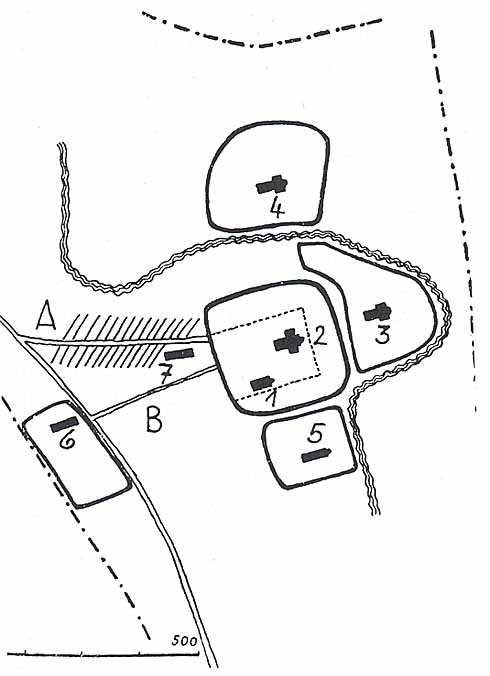

The only 'hard' evidence for the existence of the cross of churches in Utrecht is provided by the four eleventh-century churches themselves. The Pieterskerk in the east, the Mariakerk in the west, the Janskerk in the north and the church of Paulus in the south stand at the four cardinal points around the cathedral, the axis of the cruciform configuration of churches.17

When Bishop Conrad (1076-99) added the Mariakerk, and so completing the arrangement, he fulfilled the plan initiated under Bishop Bernold.18 Even the consecration of the new church to the mother of Christ, Mary, was based on a criteria established by Bernold. Mary had been one of the patron saints of the old cathedral church of Salvator which, as we have already seen, provided the dedications of the three other churches which formed the 'cross'.

That Bishop Bernold presided over the foundation of the other three churches bas long been accepted, and for good reason. That king Henry III bas also to be considered as the chief patron can, in my opinion, be supported not only from the evidence outlined above, but also on the basis of the wider implications of the choice of such a plan and the forms of the individual churches.19

CROSSES OF CHURCHES

Only two other instances of programmes for the creation of crosses of churches are known from the Holy Roman Empire at Bamberg and Paderborn. The imperial implications of these projects were resonant at Utrecht, and certainly provided the motive for the building of a cross of churches there. At Bamberg and Paderborn, as at Utrecht, the cathedral stood at the centre of a cross spanning the city, each of the four arms of which were marked by collegiate churches or cloisters. 2l In all three cases the construction of the cross of churches was begun in the first half of the eleventh century. In Bamberg and Paderborn the king of the Holy Roman Empire was active in the foundation and construction of the new churches.22 This may also be the case in Utrecht. The three cities enjoyed similar status in the first half of the eleventh century: they are all episcopal seats with which the king had both personal concerns and a political interest in their position and livelihood.

With the exception of the complexes at Bamberg, Paderborn and Utrecht, all the other crosses of churches in the eleventh century Holy Roman Empire of a scale larger than that of a cathedral immunity or a monastic complex,23 came into being through the restructuring and transformation of pre-existing churches.

Perhaps the earliest example of this kind is the so-called 'Kirchenkranz', which is interpreted as a reference to the Heavenly Jerusalem. It is assumed that the 'wreaths' of churches which lay around the cathedrals of Cologne and Strasbourg were transformed but not expressly built, to farm crosses.

Similarly triangles of churches were arranged in symbolic reference to the Holy Trinity. Such a configuration of churches within the monastic enclosure at Fulda was modified to form a cross during the eleventh century.25

FIG. I. Utrecht, diagrammatic plan showing the Cross of Churches: I. St Salvator or OId

Minster; 2. Cathedralof St Maarten; . 3. Pieterskerk; 4. Janskerk; 5. Pauluskerk; 6. Mariakerk; B. 'Via Triumphalis' or 'procession route of the Emperor' (from

E. Herzog, Die ottonische Stadt (Berlin 1964), p.150

At Hildesheim a sequence of churches built around the cathedral in no apparent order was later fitted into a cross formation.26

THE CROSS AS IDEOGRAM

Just like the arrangement of churches at the vertexes of a hypothetical triangle, the position of churches at the extremities and the intersection of a hypothetical cruciform bas to be interpreted as an ideogram. That is to say that the architectural patron expressly wanted to refer to one or more specific concepts with one or other configuration. The ideogram of the cruciform is much richer in referential meanings than that of the triangle which I must assume referred exclusively to the Holy Trinity and the related theological connotations.27

The cross of churches refers not only to specific elements of the Christian religious tradition but also to cosmology and politico-historical ideals and events. While the above-mentioned references to Christian theology are historically best characterized by the concept 'clerical-allegorical', the designation 'politico-allegorical' does most justice to the specifically medieval references to cosmology and politico-historical nature.28

In the medieval world the cruciform figuration is naturally associated with the cross of Christ. The monks and canons who inhabited the ecclesiastical institutions of the cross of churches in Paderborn were known as 'servants of the crucified'.29

The sign of the cross was first and foremost the standard of the triumphant Saviour who with it had conquered death and its cause, sin. Alongside this soteriological interpretation, the apotropeic power of the cross must not be overlooked.

(103)

In this case the sign of the cross is regarded as a defence against the powers of evil, particularly against those forces which threaten the salvation of the human soul. This talismanic magic effect of the Christian cross has its origins in pre-Christian cultures and may be derived from symbols of salvation found in prehistoric art. Closely related to the apotropeic power of the cross is its use in the consecration of a specific area. The ancient custom of creating a 'templum', an angle piece of heaven on earth, by using a cruciform was assumed by Christianity and prominently deployed in the laying out of churches, monastic complexes and other foundations which are earthly reflections of the heavenly Jerusalem.

As the most essential characteristic of the structure of the Heavenly City, the cross refers to the eschatology, the end of time when Christ will appear in heaven with the trophy of the cross and when the Heavenly Jerusalem will descend to earth to receive the righteous as the fellow citizens of God and his Saints. The written tradition surrounding the cross of Paderborn contains references to the eschatological significance of the arrangement of the churches.

Utrecht

In the first paragraph of this study, I tried to show that the occasion of the foundation of the cross of churches in Utrecht was the interment of the entrails of emperor Conrad III in the cathedral there. The cross of Bamberg was established along with its Bishopric, and that of Paderborn is associated with the 'Renovatio' of the see there. Despite the different circumstances, the foundation of each of the three crosses enjoyed the harmonious co-operation of emperor and Bishop and are perhaps best viewed against the political contexts in which they took place. Each project is associated with the élite patronage of the imperial court, be it on a central level as at Bamberg, or a regional level as at Paderborn and Utrecht.

THE CROSS OF CHURCHES: AN IMAGE OF THE CHURCH

At both Paderborn and Utrecht, one church in each sequence was appointed 'ecclesia mater'. At Paderborn the cathedral functioned as such; in Utrecht the role was assumed by the former episcopal church which was known by the name of 'Oldminster'. There is, however, one essential difference: at Paderborn, the main invocation was transferred from the cathedral to both the named churches; at Utrecht, however, each of the four churches were dedicated to one of the secondary patrons of the Oldminster (Pl. III).33

While at Padertborn the main patron of the newly-founded churches is the same though the church buildings themselves were quite different from each other, at Utrecht the opposite can be observed. As far as can be judged by their architecture, the churches dedicated to St Peter, St Paul and St John the Baptist had rather similar forms. The fact that the Mariakerk is an exception to this is undoubtedly a consequence of the fact that it was built some decades later, under the authority of a different emperor and Bishop.

It is not only striking that the three churches built following the episcopal funerary-church dedicated to Peter display the same principal forms. It is equally remarkable

(under construction)

terug naar boven

|

|